Three exciting Stories by Christopher Lynch — author, pilot and co-founder of the Midway Historians

Pierce O'Carroll

The story of Chicago is the tale of adventurers, of people immigrating from other countries or moving west from Eastern Cities, and finding a future along the shores of Lake Michigan. Carl Sandburg described Chicago as the "City of Broad Shoulders", but it was also the city of possibility to the many new arrivals. For the Irish, Chicago was a town where one could compete on a level playing field, not burdened by a penal system they had known in Ireland, which was rigged to favor those of power, privilege, and class. And it was such people of vision that turned Chicago into the World Class city that it is today.

This is the story of one Irishman's arrival to the big city, who came to seek the American dream, and found it in the skies above Chicago.

Pierce O'Carroll was born in Rathdowney, County Leix, on the border of Tipperary, in 1899. Son of a farmer, he was almost destined to spend the rest of his life working the land, except for an event that would change his life forever.

One day, as a young man of 17, while toiling in the fields, he heard the strange drone of an engine. He was startled to see a biplane flying overhead, the first airplane he had ever seen. In an instant, his life was forever changed, for it was at that moment Pierce O'Carroll chose to become a pilot.

He immigrated to the United States in 1925, and found work as a streetcar motor-man on Michigan Avenue. Yet, his dream of flying brought him to the Southwest side of Chicago, to Ashburn field, now a long since vanished airport at 79th and Cicero. After his first flying lesson, O'Carroll was looking forward to the next one. However, when he went out to the airport, his instructor was late. Pierce got impatient, and decided to take the plane up anyway. When the instructor finally showed up, he saw his student doing turns and rolls in the skies above. After landing, there was only one thing the instructor could say to O'Carroll: "You passed."

In 1926, the city of Chicago leased an onion field from the Board of Education at 63rd and Cicero and put down Cinder runways. This modest attempt was called Chicago Municipal Airport, known to us today as Midway Airport. O'Carroll opened a business called Monarch Air Service in a hanger on the field, which serviced airplanes for the still experimental enterprise of aviation. O'Carroll's only real competition was a small fledgling airline called United, which was located in the next hanger.

The Monarch hanger became a place where later aviation heroes, such as Jimmy Doolittle and Bill Lear could be found, swapping stories of their exploits in the air.

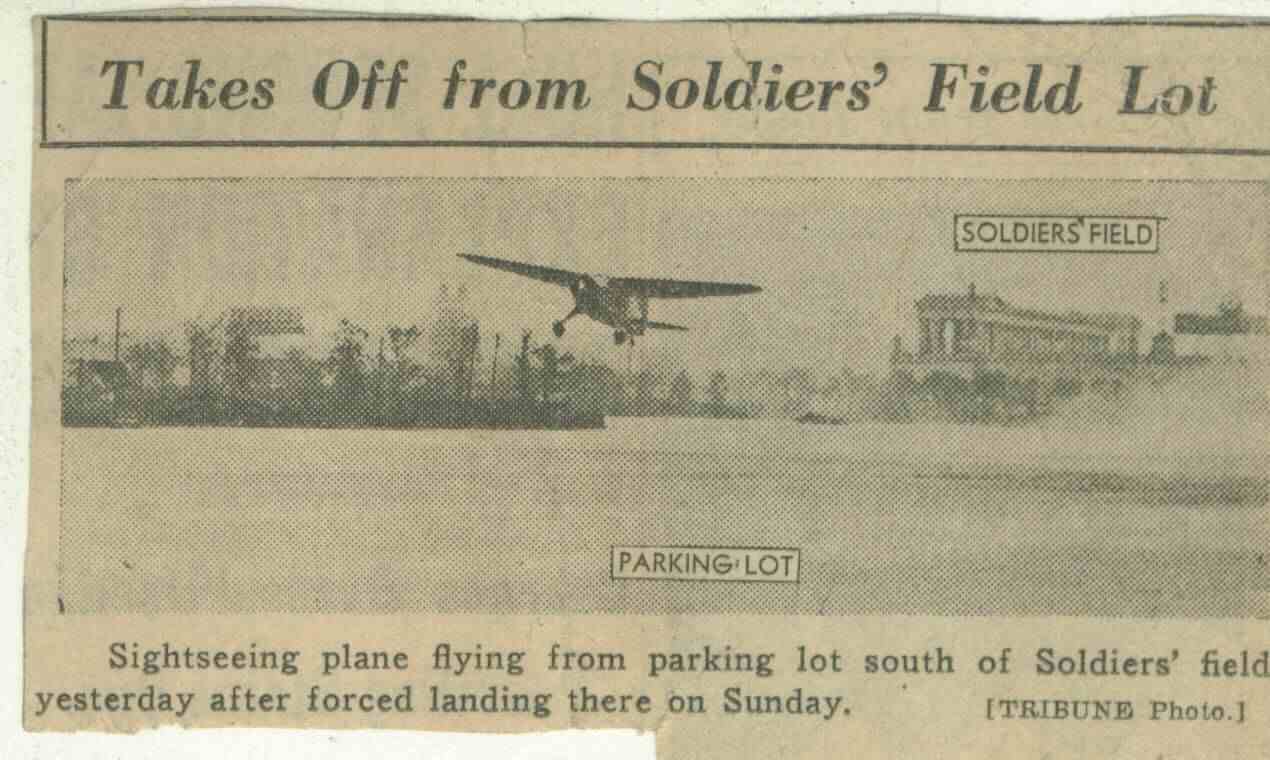

Aviation in the early barnstorming days was not the sleek comfortable mode of travel it is today. In fact, it was a grimy, tough business, of engines that could blow out at any time, and usually did. Once, O'Carroll was flying over the city, when his engine failed. He made an emergency landing in front of Soldier field, in the parking lot. A crowd gathered, to see him, his tool kit by his side, as he repaired an engine. Someone asked him how he was going to get the plane out of the parking lot. O'Carroll said he was going to bring it out the same way he brought it in, by taking it off, even though the path out was short, and marred by trees. He fired up the engine, and after a wave to the crowd, his airplane roared into the air, clearing the trees. A few weeks later, another pilot put his plane down in the same parking lot, yet he didn't have the nerve to take it off. So, he called O'Carroll, who did it for him.

Phil Felper, a pilot who first met O'Carroll in the 1930s, talked of his drive and vision. "Pierce would say, `If the birds could fly, I could fly.' A guy like him drove you."

In the 1930s, the only people who flew were either airmail pilots, or the very rich. But O'Carroll wanted aviation to be enjoyed by anyone, regardless of economics or class. He started a sightseeing business, which gave flights over the city on the weekends. People from all over Chicago would come out to a little wooden shack on the airport, where his wife Rose from County Meath would sell tickets, for $3.50. The DC-3, which could carry 21 people, would glide over the lakefront as myriads of passengers marveled at the skyline on the first flight of their lives.

Sightseeing was one thing, but O'Carroll saw the true potential of aviation as a way to bring people on vacations to warm places on the weekends, and do it quickly and cheaply. He began to fly to Miami after World War II, and he made it affordable for his passengers. He began to realize his dream of making aviation accessible to the common man.

This new type of airline was known as non-scheduled airlines, or "non-skeds", and their arrival on the transportation scene was not universally welcomed. Although O'Carroll's flights were booked solid, as young honeymooners and families took their first Florida vacations, the more established airlines, (whose businesses were being undercut by these cheap flights) began to lobby Congress to regulate the non-skeds out of business.

O'Carroll began to feel the pressure of this lobbying, and not being shy, he sent a letter to President Harry S. Truman in 1950: He wrote that from the moment he stepped off the boat from Ireland, "I was fired with ambition to make a name for myself in the great United States", and that from the moment he had received his pilot's license, "from that day to this, my whole thought, word and deeds were for the good of aviation."

O'Carroll noted that the dream of open and free competition in the skies was beginning to erode due to government interference, and that the public would suffer the most from such bureaucratic intrusions. O'Carroll felt that this was in direct opposition to the dream of inexpensive air travel. O'Carroll relayed how he had spent the last "twenty-five years of the best part of a man's life devoted to an idea-progress in aviation to provide air transportation to the working man, his wife and family...I feel proud to be able to provide low cost air transportation."

Such competition, O'Carroll reiterated, gave "the working man air transportation at low cost. Let's all work to provide air transportation at low cost, even lower than at present, if possible. It's the American way of life."

There is no record of a response to this letter, but the regulatory climate became so unfavorable to the non-skeds that O'Carroll would get out of it completely in 1951. O'Carroll's dream of cheap fares for the common man had run out of fuel.

Unfortunately, O'Carroll would never live to see the re-emergence of low cost air travel. It was not until 1978 that the government deregulated the transportation industry, when Americans of all economic strata would again have the opportunity to take advantage of inexpensive fares.

Ironically, this pilot, who had spent thousands of hours in the air during aviation's dangerous days, died on the ground. In 1961 O'Carroll suffered a fatal stroke in New York City.

Pierce O'Carroll loved Chicago, especially as he soared above its majestic skyline in Monarch's DC-3. He was gratified that, as he once wrote, "I have flown more first riders over the city of Chicago than any pilot in the United states, and I am proud of it."

Even in death he flew back to his beloved city. On a December night, when the plane bearing his casket flew into Midway on final approach, the runway lights —like the beams of lighthouses on the ocean —guided this ship of the air to its port, and Scotty home, through the fog.

The controllers in the tower were ready; they had been waiting and watching. For when his plane’s wheels touched down, and the aircraft rolled to a halt, a switch was thrown and the runway lights dimmed, a tribute from his friends at Midway to this Tipperary farmer who had been born before the Wright Brothers took off at Kitty Hawk, and died the same year America sent her first astronaut into space.

After the priest recited the Latin prayers at the graveside, and the crowd of mourners had begun to break up, the muffled roar of an aircraft engine could be heard as a plane came into view over Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. Pierce’s friend Joey Bishop circled the gravesite, and before departing, dipped his wings in a final goodbye, from one pilot to another.

The story of Chicago is the tale of adventurers, of people immigrating from other countries or moving west from Eastern Cities, and finding a future along the shores of Lake Michigan. Carl Sandburg described Chicago as the "City of Broad Shoulders", but it was also the city of possibility to the many new arrivals. For the Irish, Chicago was a town where one could compete on a level playing field, not burdened by a penal system they had known in Ireland, which was rigged to favor those of power, privilege, and class. And it was such people of vision that turned Chicago into the World Class city that it is today.

This is the story of one Irishman's arrival to the big city, who came to seek the American dream, and found it in the skies above Chicago.

Pierce O'Carroll was born in Rathdowney, County Leix, on the border of Tipperary, in 1899. Son of a farmer, he was almost destined to spend the rest of his life working the land, except for an event that would change his life forever.

One day, as a young man of 17, while toiling in the fields, he heard the strange drone of an engine. He was startled to see a biplane flying overhead, the first airplane he had ever seen. In an instant, his life was forever changed, for it was at that moment Pierce O'Carroll chose to become a pilot.

He immigrated to the United States in 1925, and found work as a streetcar motor-man on Michigan Avenue. Yet, his dream of flying brought him to the Southwest side of Chicago, to Ashburn field, now a long since vanished airport at 79th and Cicero. After his first flying lesson, O'Carroll was looking forward to the next one. However, when he went out to the airport, his instructor was late. Pierce got impatient, and decided to take the plane up anyway. When the instructor finally showed up, he saw his student doing turns and rolls in the skies above. After landing, there was only one thing the instructor could say to O'Carroll: "You passed."

In 1926, the city of Chicago leased an onion field from the Board of Education at 63rd and Cicero and put down Cinder runways. This modest attempt was called Chicago Municipal Airport, known to us today as Midway Airport. O'Carroll opened a business called Monarch Air Service in a hanger on the field, which serviced airplanes for the still experimental enterprise of aviation. O'Carroll's only real competition was a small fledgling airline called United, which was located in the next hanger.

The Monarch hanger became a place where later aviation heroes, such as Jimmy Doolittle and Bill Lear could be found, swapping stories of their exploits in the air.

Aviation in the early barnstorming days was not the sleek comfortable mode of travel it is today. In fact, it was a grimy, tough business, of engines that could blow out at any time, and usually did. Once, O'Carroll was flying over the city, when his engine failed. He made an emergency landing in front of Soldier field, in the parking lot. A crowd gathered, to see him, his tool kit by his side, as he repaired an engine. Someone asked him how he was going to get the plane out of the parking lot. O'Carroll said he was going to bring it out the same way he brought it in, by taking it off, even though the path out was short, and marred by trees. He fired up the engine, and after a wave to the crowd, his airplane roared into the air, clearing the trees. A few weeks later, another pilot put his plane down in the same parking lot, yet he didn't have the nerve to take it off. So, he called O'Carroll, who did it for him.

Phil Felper, a pilot who first met O'Carroll in the 1930s, talked of his drive and vision. "Pierce would say, `If the birds could fly, I could fly.' A guy like him drove you."

In the 1930s, the only people who flew were either airmail pilots, or the very rich. But O'Carroll wanted aviation to be enjoyed by anyone, regardless of economics or class. He started a sightseeing business, which gave flights over the city on the weekends. People from all over Chicago would come out to a little wooden shack on the airport, where his wife Rose from County Meath would sell tickets, for $3.50. The DC-3, which could carry 21 people, would glide over the lakefront as myriads of passengers marveled at the skyline on the first flight of their lives.

Sightseeing was one thing, but O'Carroll saw the true potential of aviation as a way to bring people on vacations to warm places on the weekends, and do it quickly and cheaply. He began to fly to Miami after World War II, and he made it affordable for his passengers. He began to realize his dream of making aviation accessible to the common man.

This new type of airline was known as non-scheduled airlines, or "non-skeds", and their arrival on the transportation scene was not universally welcomed. Although O'Carroll's flights were booked solid, as young honeymooners and families took their first Florida vacations, the more established airlines, (whose businesses were being undercut by these cheap flights) began to lobby Congress to regulate the non-skeds out of business.

O'Carroll began to feel the pressure of this lobbying, and not being shy, he sent a letter to President Harry S. Truman in 1950: He wrote that from the moment he stepped off the boat from Ireland, "I was fired with ambition to make a name for myself in the great United States", and that from the moment he had received his pilot's license, "from that day to this, my whole thought, word and deeds were for the good of aviation."

O'Carroll noted that the dream of open and free competition in the skies was beginning to erode due to government interference, and that the public would suffer the most from such bureaucratic intrusions. O'Carroll felt that this was in direct opposition to the dream of inexpensive air travel. O'Carroll relayed how he had spent the last "twenty-five years of the best part of a man's life devoted to an idea-progress in aviation to provide air transportation to the working man, his wife and family...I feel proud to be able to provide low cost air transportation."

Such competition, O'Carroll reiterated, gave "the working man air transportation at low cost. Let's all work to provide air transportation at low cost, even lower than at present, if possible. It's the American way of life."

There is no record of a response to this letter, but the regulatory climate became so unfavorable to the non-skeds that O'Carroll would get out of it completely in 1951. O'Carroll's dream of cheap fares for the common man had run out of fuel.

Unfortunately, O'Carroll would never live to see the re-emergence of low cost air travel. It was not until 1978 that the government deregulated the transportation industry, when Americans of all economic strata would again have the opportunity to take advantage of inexpensive fares.

Ironically, this pilot, who had spent thousands of hours in the air during aviation's dangerous days, died on the ground. In 1961 O'Carroll suffered a fatal stroke in New York City.

Pierce O'Carroll loved Chicago, especially as he soared above its majestic skyline in Monarch's DC-3. He was gratified that, as he once wrote, "I have flown more first riders over the city of Chicago than any pilot in the United states, and I am proud of it."

Even in death he flew back to his beloved city. On a December night, when the plane bearing his casket flew into Midway on final approach, the runway lights —like the beams of lighthouses on the ocean —guided this ship of the air to its port, and Scotty home, through the fog.

The controllers in the tower were ready; they had been waiting and watching. For when his plane’s wheels touched down, and the aircraft rolled to a halt, a switch was thrown and the runway lights dimmed, a tribute from his friends at Midway to this Tipperary farmer who had been born before the Wright Brothers took off at Kitty Hawk, and died the same year America sent her first astronaut into space.

After the priest recited the Latin prayers at the graveside, and the crowd of mourners had begun to break up, the muffled roar of an aircraft engine could be heard as a plane came into view over Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. Pierce’s friend Joey Bishop circled the gravesite, and before departing, dipped his wings in a final goodbye, from one pilot to another.

Crossroads of the World

The frenzied activity that World War II brought to Chicago's airport did not cease when peace came. On the contrary, it became busier than ever at Chicago's newly-named Midway Airport.

Retired commercial and corporate pilot Philip Felper relates: "It was really busy. Eastern Airlines and some of the others had a plane approaching or taking off every few minutes. If the weather got bad, you had yourself a real job. The approach came right over the top of the end hangar on the field, the American Airlines hangar, and if you wanted a thrill you'd be in that hangar; when you heard the engines running like hell when the weather was bad, you'd run out to a side of the hangar. I'm surprised that nobody hit the hangar. But that's the way it was in this busiest airport in the world.

"This was one of the best fields in the country to 'and at because you had a place to eat, you could get People to work on your airplane, get fuel. For fun, there was that fella Roscoe Turner who carried a full-grown lion with him, and he stopped at Chicago many times, and he'd come off his plane with the lion. It kept you away from his plane, anyhow."

Midway was fast becoming the center of aviation in the United States, but there were still some issues that had to be addressed. Since 1926, the City of Chicago had leased Midway from the Board of Education. Consequently, for the next 20 years,Hale Grammar School shared its land with the airport.

In the beginning, when Midway was in its infancy, there was little concern about this rather unusual arrangement. But as the field expanded, and the world's most active runways ran right next to the school, parents and administrators began to get uneasy. For pilots like Felper it was about time. "There was a large school [Hale] right down here on the corner of 63rd and Central just on the airport side. When all the kids came out for recess they'd come running out where the airplanes would be flying around 'em. It was a strange setup but the Board of Education didn't seem to worry too much."

In 1946, Robert Platt, hired by the Association of American Geographers for the Clearing District, wrote a report that highlighted the Hale School's peculiar location a few feet from a working runway after airport expansion. Platt wrote that "when the wind is easterly, planes warm up by the school making noise, when westerly, they fly over it."

According to Robert "Moose" Hill, a Hale alumnus, students in the classrooms could hear airplanes revving their engines before takeoff, and students "could hear the window glass hum, see the ink in your inkwell ripple, and feel the room vibrate.

"They wanted to close Hale School down because of all the noise around it. The parents went to the Board of Education who told them they'd close the School and get the kids into schools that were a lot quieter. The parents started realizing that their kids were going to get split up into different schools because the Board was not going to build another school for them. The parents complained again. The Board said you're the ones who wanted to close the school because of the noise and that's what we're going to do.

"The parents kept up the pressure until Mayor Martin J. Kennelley said 'the children come first ahead of big business. Hale School will stay open until a new school is built.'"

"And the arrangement that was made was incredible. The two runways that straddled Hale School were to be closed for the hours that the children were in school. They might just as well put up street signs saying 'No airplanes may use the prevailing runways of the busiest airport in the world on school days when children are present.' It's unbelievable but it sure made them hurry up and build a new school."

There was not much public flying until after World War II. It was very expensive; only the wealthy and many movie stars flew as a substitute for the streamliners—first class train travel.

The frenzied activity that World War II brought to Chicago's airport did not cease when peace came. On the contrary, it became busier than ever at Chicago's newly-named Midway Airport.

Retired commercial and corporate pilot Philip Felper relates: "It was really busy. Eastern Airlines and some of the others had a plane approaching or taking off every few minutes. If the weather got bad, you had yourself a real job. The approach came right over the top of the end hangar on the field, the American Airlines hangar, and if you wanted a thrill you'd be in that hangar; when you heard the engines running like hell when the weather was bad, you'd run out to a side of the hangar. I'm surprised that nobody hit the hangar. But that's the way it was in this busiest airport in the world.

"This was one of the best fields in the country to 'and at because you had a place to eat, you could get People to work on your airplane, get fuel. For fun, there was that fella Roscoe Turner who carried a full-grown lion with him, and he stopped at Chicago many times, and he'd come off his plane with the lion. It kept you away from his plane, anyhow."

Midway was fast becoming the center of aviation in the United States, but there were still some issues that had to be addressed. Since 1926, the City of Chicago had leased Midway from the Board of Education. Consequently, for the next 20 years,Hale Grammar School shared its land with the airport.

In the beginning, when Midway was in its infancy, there was little concern about this rather unusual arrangement. But as the field expanded, and the world's most active runways ran right next to the school, parents and administrators began to get uneasy. For pilots like Felper it was about time. "There was a large school [Hale] right down here on the corner of 63rd and Central just on the airport side. When all the kids came out for recess they'd come running out where the airplanes would be flying around 'em. It was a strange setup but the Board of Education didn't seem to worry too much."

In 1946, Robert Platt, hired by the Association of American Geographers for the Clearing District, wrote a report that highlighted the Hale School's peculiar location a few feet from a working runway after airport expansion. Platt wrote that "when the wind is easterly, planes warm up by the school making noise, when westerly, they fly over it."

According to Robert "Moose" Hill, a Hale alumnus, students in the classrooms could hear airplanes revving their engines before takeoff, and students "could hear the window glass hum, see the ink in your inkwell ripple, and feel the room vibrate.

"They wanted to close Hale School down because of all the noise around it. The parents went to the Board of Education who told them they'd close the School and get the kids into schools that were a lot quieter. The parents started realizing that their kids were going to get split up into different schools because the Board was not going to build another school for them. The parents complained again. The Board said you're the ones who wanted to close the school because of the noise and that's what we're going to do.

"The parents kept up the pressure until Mayor Martin J. Kennelley said 'the children come first ahead of big business. Hale School will stay open until a new school is built.'"

"And the arrangement that was made was incredible. The two runways that straddled Hale School were to be closed for the hours that the children were in school. They might just as well put up street signs saying 'No airplanes may use the prevailing runways of the busiest airport in the world on school days when children are present.' It's unbelievable but it sure made them hurry up and build a new school."

There was not much public flying until after World War II. It was very expensive; only the wealthy and many movie stars flew as a substitute for the streamliners—first class train travel.

A Takeoff and a Landing

Pierce O’Carroll learned how to fly at Ashburn field in Chicago in the barnstorming era of the 1920s, when airplanes and engines were unreliable and a pilot had to live by his wits. Although aviation had advanced in the decades he had been flying, Pierce was still a barnstormer at heart, and would use those skills to get himself out of tough situations. Tom O’Hara, the Irish cop whose beat was Midway Airport, relayed to his son Jim (who told me the story fifty years later) about one such incident, when Pierce was taking off from Midway in his Lockeed Electra, the same type of ship that Amelia Earhart flew in on her ill-fated flight around the world in 1937.

Pierce, whose attitude towards altitude was a lot like his feeling about money in a bank-you could always draw upon it. So, on his takeoffs, he would point his aircraft on a steep angle, gaining as much altitude as possible.

For any aircraft, the takeoff is the most critical point in any flight. And on that particular takeoff, Pierce’s aircraft’s engine died. Needless to say, his options were extremely limited. He was too low to make an attempt to circle back to the airport, and had run out of runway.

His aircraft was now hanging in the air, with the laws of physics about to go into motion, with gravity about to pull the aircraft downward. An emergency landing would be tricky, since unlike the airport’s early days, when it was bordered by open fields, the land had since been developed, with stores, hotels, restaurants and houses.

Pierce had less than a second to make a decision that could mean the difference between life and death. His choice was the most outrageous of all.

Pierce had studied the capacity of his aircraft’s engine, knowing that the Electra’s engine had incredible horsepower. So, by using the momentum of the plane’s horsepower, he looped the Electra.

A moment before, he had no runway left on his path; yet now, thanks to his loop, he was coasting upside down through the air above the very runway from which he had just taken off.

After leveling the aircraft, he landed, with a few hundred feet of runway left to spare. Pierce had created runway where a moment before there was none. Officer O’Hara had never seen anything like it.

When it counted, Pierce delivered. Yet even he could have a bad day.

The controllers at Midway tower all knew Pierce, calling him by his nickname "Scotty". Often, if he was on a final approach on a dark night, the controller would often say, "Scotty, do you have your gear down?" Pierce, being an old pro, was often annoyed at this, and would say on the radio, "Of course I have my gear down!"

This exchange happened several times over the course of a few months. Then, on a particular evening, Pierce was coming in for a landing. The controller in the tower, knowing how irritated Pierce would be if he mentioned the gear, remained mum.

The plane came in for a landing. As it was touching down, there was a shower of sparks erupting from the bottom of the fuselage as the aircraft slid down the runway.

When the airplane came to a halt, the controller picked up the microphone and said, after a prolonged pause,

"Scotty, do you have your gear down?"

The silence from Pierce's plane was deafening, but it wasn't long before Pierce got the plane off the runway, and made it to a phone. He called the tower and gave them a piece of his mind. Needless to say, he wasn't amused.

Pierce O’Carroll learned how to fly at Ashburn field in Chicago in the barnstorming era of the 1920s, when airplanes and engines were unreliable and a pilot had to live by his wits. Although aviation had advanced in the decades he had been flying, Pierce was still a barnstormer at heart, and would use those skills to get himself out of tough situations. Tom O’Hara, the Irish cop whose beat was Midway Airport, relayed to his son Jim (who told me the story fifty years later) about one such incident, when Pierce was taking off from Midway in his Lockeed Electra, the same type of ship that Amelia Earhart flew in on her ill-fated flight around the world in 1937.

Pierce, whose attitude towards altitude was a lot like his feeling about money in a bank-you could always draw upon it. So, on his takeoffs, he would point his aircraft on a steep angle, gaining as much altitude as possible.

For any aircraft, the takeoff is the most critical point in any flight. And on that particular takeoff, Pierce’s aircraft’s engine died. Needless to say, his options were extremely limited. He was too low to make an attempt to circle back to the airport, and had run out of runway.

His aircraft was now hanging in the air, with the laws of physics about to go into motion, with gravity about to pull the aircraft downward. An emergency landing would be tricky, since unlike the airport’s early days, when it was bordered by open fields, the land had since been developed, with stores, hotels, restaurants and houses.

Pierce had less than a second to make a decision that could mean the difference between life and death. His choice was the most outrageous of all.

Pierce had studied the capacity of his aircraft’s engine, knowing that the Electra’s engine had incredible horsepower. So, by using the momentum of the plane’s horsepower, he looped the Electra.

A moment before, he had no runway left on his path; yet now, thanks to his loop, he was coasting upside down through the air above the very runway from which he had just taken off.

After leveling the aircraft, he landed, with a few hundred feet of runway left to spare. Pierce had created runway where a moment before there was none. Officer O’Hara had never seen anything like it.

When it counted, Pierce delivered. Yet even he could have a bad day.

The controllers at Midway tower all knew Pierce, calling him by his nickname "Scotty". Often, if he was on a final approach on a dark night, the controller would often say, "Scotty, do you have your gear down?" Pierce, being an old pro, was often annoyed at this, and would say on the radio, "Of course I have my gear down!"

This exchange happened several times over the course of a few months. Then, on a particular evening, Pierce was coming in for a landing. The controller in the tower, knowing how irritated Pierce would be if he mentioned the gear, remained mum.

The plane came in for a landing. As it was touching down, there was a shower of sparks erupting from the bottom of the fuselage as the aircraft slid down the runway.

When the airplane came to a halt, the controller picked up the microphone and said, after a prolonged pause,

"Scotty, do you have your gear down?"

The silence from Pierce's plane was deafening, but it wasn't long before Pierce got the plane off the runway, and made it to a phone. He called the tower and gave them a piece of his mind. Needless to say, he wasn't amused.

Christopher Lynch is author of Chicago's Midway Airport: The First Seventy-Five Years and When Hollywood Landed at Chicago's Midway Airport: The Photos and Stories of Mike Rotunno. Chris also co-authored the new book, "Now Arriving: Traveling To And From Chicago By Air, 90 Years Of Flight" with Neal Samors

Copyright ©2009-2020 The Midway Historians. All rights Reserved